Fabaceae

Legume Family

The Fabaceae or Leguminosae, commonly known as the legume, pea, or bean family, is the third-largest family of flowering plants, with over 19,500 species across approximately 750 genera. This economically and ecologically important family includes food crops, forage plants, timber trees, medicinal plants, and many species capable of nitrogen fixation through symbiotic relationships with bacteria.

Overview

The Fabaceae family is one of the most diverse and widespread plant families, found in almost all terrestrial habitats from tropical rainforests to deserts and alpine regions. The family's remarkable success is largely attributed to its ability to form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, allowing many legumes to thrive in nitrogen-poor soils and serve as pioneer species in ecological succession.

Legumes have played a crucial role in human civilization for thousands of years. They were among the earliest plants domesticated by humans, with evidence of cultivation dating back to 10,000 BCE. Today, legumes remain essential components of agricultural systems worldwide, providing protein-rich foods, animal fodder, green manure, timber, medicines, and ornamental plants.

The family's economic importance extends beyond food production. Many legumes are used in agroforestry systems, soil improvement, and land reclamation due to their nitrogen-fixing abilities. Legume trees provide valuable timber, while numerous species yield dyes, tannins, resins, insecticides, and medicinal compounds. The family also includes many popular ornamental plants cultivated for their beautiful flowers and foliage.

Quick Facts

- Scientific Name: Fabaceae (formerly Leguminosae)

- Common Name: Legume family, Pea family, Bean family

- Number of Genera: Approximately 750

- Number of Species: Over 19,500

- Distribution: Worldwide, on all continents except Antarctica

- Evolutionary Group: Eudicots - Rosids

Key Characteristics

Growth Form and Habit

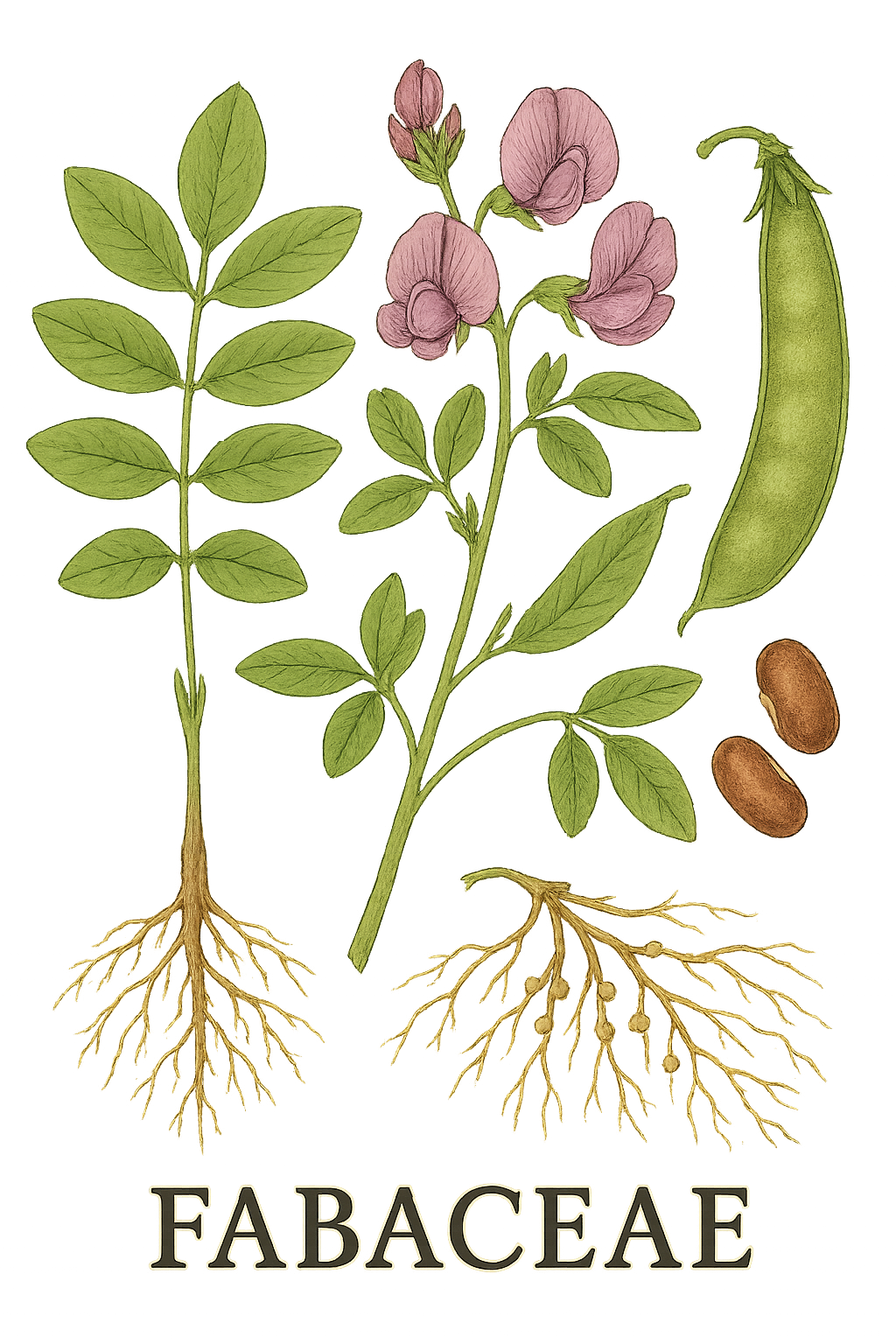

The Fabaceae family encompasses an extraordinary diversity of growth forms, including annual and perennial herbs, shrubs, woody vines (lianas), and trees of various sizes from small understory species to emergent canopy giants. This diversity reflects the family's evolutionary adaptability to different ecological niches. Many herbaceous legumes have extensive root systems with nitrogen-fixing nodules, while woody species often develop deep taproots. Some genera, like Acacia in dry environments, have evolved specialized adaptations such as phyllodes (modified leaf stalks) instead of true leaves to reduce water loss.

Leaves

Leaves in the Fabaceae family are typically alternate and stipulate, with the stipules varying from small and inconspicuous to large and leaf-like. The leaves are most commonly compound, either pinnate (feather-like with leaflets arranged along a central axis) or palmate (with leaflets radiating from a single point). Some species have bipinnate leaves (twice compound), while others have simple leaves or phyllodes. Many legumes exhibit nyctinastic movements, with leaflets folding together at night or when touched (as in the sensitive plant, Mimosa pudica).

Leaf modifications are common in the family and often reflect adaptations to specific environments. These include:

- Tendrils derived from leaflet modifications (as in Pisum and Vicia)

- Phyllodes, which are flattened leaf stalks functioning as leaves (common in some Acacia species)

- Reduced or absent leaves in some desert-adapted species

- Spines derived from stipule modifications (as in Robinia)

Flowers

Flowers in the Fabaceae family are typically bisexual and pentamerous (based on a plan of five), with a distinctive structure that varies among the three traditionally recognized subfamilies. The flowers are usually arranged in racemes, panicles, spikes, or heads, though solitary flowers occur in some species.

The three main flower types in Fabaceae correspond to the traditional subfamilies:

- Papilionoid flowers (subfamily Faboideae): These have a distinctive "pea-like" or "butterfly-like" zygomorphic structure with five petals arranged in a standard (banner), two wings, and two lower petals fused to form a keel that encloses the stamens and pistil. The calyx is typically tubular with five lobes. Most papilionoid flowers have ten stamens, either all fused into a tube (monadelphous) or with nine fused and one free (diadelphous).

- Mimosoid flowers (subfamily Mimosoideae): These are small, actinomorphic (radially symmetrical) flowers typically arranged in dense globular heads or spikes. They have a small calyx and corolla, but the numerous stamens with their long, colorful filaments are the showy part of the flower. The petals are often fused at the base.

- Caesalpinioid flowers (subfamily Caesalpinioideae): These show intermediate characteristics, typically with five separate petals arranged in a bilateral symmetry that is less pronounced than in papilionoid flowers. The uppermost petal is innermost in the bud (unlike in papilionoid flowers where it is outermost). Stamens are usually ten or fewer and may be of unequal lengths.

The gynoecium in all Fabaceae consists of a single carpel that develops into the characteristic legume fruit. The ovary is superior, with a terminal style and stigma, and contains one to many ovules arranged along the ventral suture.

Fruits and Seeds

The defining fruit type of the Fabaceae family is the legume (also called a pod), a dry dehiscent fruit derived from a single carpel that typically splits along two sutures to release the seeds. However, the family exhibits remarkable diversity in fruit morphology, with numerous modifications of the basic legume structure:

- Typical dehiscent legumes that split along both sutures (e.g., garden pea, beans)

- Indehiscent legumes that do not open at maturity (e.g., peanut)

- Loments, which break transversely into one-seeded segments (e.g., Desmodium)

- Samaras, with wing-like extensions for wind dispersal (e.g., Dalbergia)

- Drupes, with fleshy or fibrous outer layers (e.g., Andira)

- Follicles, which split along a single suture (e.g., some Astragalus)

Seeds of Fabaceae are typically oval to round, sometimes flattened, and vary greatly in size from tiny (as in clover) to very large (as in some tropical species). They often have a hard seed coat (testa) that provides protection and may enforce dormancy. Many legume seeds have a distinctive hilum, the scar marking the point of attachment to the fruit wall. Some species also have an aril, a fleshy outgrowth from the funiculus that may aid in seed dispersal by attracting animals.

Seed dispersal mechanisms in the family are diverse and include:

- Explosive dehiscence, where the pod suddenly splits and forcibly ejects seeds (e.g., Cytisus)

- Wind dispersal via winged or hairy fruits or seeds

- Animal dispersal through edible fruits or seeds with hooks or barbs

- Water dispersal in some riparian or coastal species

Root Nodules and Nitrogen Fixation

One of the most ecologically significant characteristics of the Fabaceae family is the ability of many species to form symbiotic relationships with nitrogen-fixing bacteria, primarily of the genus Rhizobium. These bacteria inhabit specialized structures called nodules that develop on the roots of host plants. Within these nodules, the bacteria convert atmospheric nitrogen (N₂) into ammonia (NH₃), which can be used by the plant. In exchange, the plant provides carbohydrates and other nutrients to the bacteria.

This symbiotic relationship allows legumes to thrive in nitrogen-poor soils and contributes significantly to global nitrogen cycling. It also makes legumes valuable in agriculture for improving soil fertility through crop rotation, intercropping, and green manuring practices. However, not all legumes form these symbiotic relationships; the ability is most common in the Papilionoideae subfamily and less frequent in the other groups.

Chemical Characteristics

The Fabaceae family is known for producing a diverse array of secondary metabolites, many of which have ecological functions in defense against herbivores and pathogens or serve as signaling molecules. These compounds also contribute to the medicinal, toxic, or nutritional properties of many legumes. Key chemical groups include:

- Alkaloids: Diverse nitrogen-containing compounds found in many genera, including the quinolizidine alkaloids in Lupinus and Cytisus, and the pyridine alkaloids in Sophora

- Isoflavonoids: Compounds with structural similarity to estrogens, particularly abundant in Glycine (soybean) and Trifolium (clover)

- Non-protein amino acids: Unusual amino acids that can be toxic to herbivores, such as canavanine in Canavalia and mimosine in Leucaena

- Lectins: Proteins that bind to specific carbohydrates, found in high concentrations in many legume seeds

- Protease inhibitors: Compounds that inhibit protein-digesting enzymes, serving as defense against insects

- Tannins: Complex polyphenolic compounds that bind to proteins, common in many woody legumes

Field Identification

Identifying members of the Fabaceae family in the field is facilitated by several distinctive features, though the diversity within the family means that not all characteristics will be present in every species. Here are key features to look for when identifying legumes:

Primary Identification Features

- Compound leaves with stipules: Most legumes have compound leaves (pinnate or palmate) with stipules at the base of the leaf stalk. The stipules may be small and inconspicuous or large and leaf-like.

- Distinctive flower structure: The papilionoid (pea-like) flower with its standard, wings, and keel is highly recognizable in many common legumes. Mimosoid flowers in dense heads with prominent stamens (as in Acacia or Mimosa) and the less regular caesalpinioid flowers (as in Cassia or Cercis) are also distinctive.

- Legume fruit: The characteristic pod fruit that splits along two seams is a defining feature of the family, though there are many variations on this basic structure.

Secondary Identification Features

- Leaf movements: Many legumes exhibit nyctinastic movements, with leaflets folding at night or when touched.

- Root nodules: If it's possible to examine the roots, the presence of nodules containing nitrogen-fixing bacteria is characteristic of many legumes.

- Alternate leaf arrangement: Legume leaves are typically arranged alternately along the stem, not opposite or whorled.

- Pulvinus: Many legumes have a swollen base at the point where the leaf attaches to the stem or where leaflets attach to the rachis, which facilitates leaf movements.

- Extrafloral nectaries: Glands that secrete nectar located outside the flowers, often on the leaf stalks or rachis, are common in many legumes, particularly in the Mimosoideae and Caesalpinioideae.

Subfamily Identification

The three traditional subfamilies of Fabaceae can often be distinguished by their flower structure:

- Faboideae (Papilionoideae): Flowers with a distinctive "pea-like" structure (standard, wings, keel); typically ten stamens, either all fused or nine fused and one free; standard petal outermost in bud.

- Mimosoideae: Small, regular (actinomorphic) flowers typically arranged in dense heads or spikes; numerous stamens with long, showy filaments; often with bipinnate leaves.

- Caesalpinioideae: Flowers with bilateral symmetry but less pronounced than in Faboideae; five petals with the uppermost petal innermost in bud; stamens often of unequal lengths.

Note: Modern classification based on molecular phylogeny has reorganized these traditional subfamilies, with Mimosoideae now included within a redefined Caesalpinioideae, but the flower types remain useful for field identification.

Seasonal Identification Tips

Fabaceae plants can be identified throughout the growing season:

- Spring: Many herbaceous legumes flower in spring. Look for the distinctive compound leaves emerging and the characteristic flowers. Spring-flowering trees like Cercis (redbud) and Robinia (black locust) are conspicuous.

- Summer: Examine fully developed leaves and flowers. Many tropical and subtropical woody legumes flower during summer.

- Fall: Fruit characteristics become important for identification as pods develop and mature. Some species have distinctive autumn coloration.

- Winter: Woody legumes can often be identified by their branching pattern, bark characteristics, and persistent fruits. Some species have distinctive thorns or spines.

Common Confusion Points

Fabaceae may sometimes be confused with:

- Sapindaceae (soapberry family): Some members have pinnately compound leaves similar to legumes but lack stipules and have different flower and fruit structures.

- Rosaceae (rose family): Some members have stipules and compound leaves, but the flower structure is different, typically with five separate petals arranged radially and numerous stamens.

- Bignoniaceae (trumpet creeper family): Some members have compound leaves, but they are typically opposite rather than alternate, and the flowers and fruits are distinctly different.

Field Guide Quick Reference

Look For:

- Compound leaves with stipules

- Alternate leaf arrangement

- Pea-like flowers or dense flower heads

- Pod fruits (legumes)

- Root nodules (if visible)

Key Variations:

- Papilionoid (pea-like) flowers

- Mimosoid flowers in dense heads

- Caesalpinioid flowers with less regular symmetry

- Pinnate, bipinnate, or palmate compound leaves

- Various pod modifications

Notable Examples

The Fabaceae family includes a wide variety of economically and ecologically important plants. Here are some notable examples from different subfamilies:

Pisum sativum

Garden Pea

This annual climbing herb has been cultivated for thousands of years for its edible seeds. It features pinnately compound leaves with terminal tendrils, large leaf-like stipules, and typical papilionoid white flowers. The fruit is a typical legume pod containing several round seeds. Garden peas are an important cool-season crop grown worldwide and were used by Gregor Mendel in his pioneering studies of inheritance.

Glycine max

Soybean

One of the world's most important legume crops, soybeans are annual herbs with trifoliate leaves and small, inconspicuous white to purple flowers. The plants are covered with fine brown or gray hairs. The fruits are short, hairy pods containing 2-4 seeds. Soybeans are a major source of plant protein and oil globally, used in numerous food products, animal feed, and industrial applications. They are particularly rich in isoflavones, compounds with potential health benefits.

Acacia senegal

Gum Arabic Tree

This small, thorny tree native to semi-arid regions of Africa is known for producing gum arabic, an important commercial product used in food, pharmaceuticals, and industrial applications. It has bipinnate leaves and small, fragrant, cream-colored flowers arranged in dense cylindrical spikes. The fruit is a flattened pod that turns brown when mature. The tree is well-adapted to drought conditions and plays an important role in preventing desertification.

Trifolium pratense

Red Clover

This short-lived perennial herb is widely cultivated as a forage crop and green manure. It has trifoliate leaves with distinctive pale markings and dense, globular heads of pink to purple papilionoid flowers. The small pods are enclosed within the persistent calyx and contain 1-2 seeds. Red clover is an important nitrogen-fixing plant used in crop rotations to improve soil fertility and is also valued for its medicinal properties, particularly its isoflavone content.

Cercis canadensis

Eastern Redbud

This small deciduous tree is native to eastern North America and is widely planted as an ornamental for its spectacular spring display of pink to purple flowers that emerge directly from the branches before the leaves appear. Unlike most legumes, it has simple, heart-shaped leaves. The flowers have the irregular structure characteristic of the Caesalpinioideae subfamily. The fruits are flattened, oblong pods that persist on the tree into winter.

Mimosa pudica

Sensitive Plant

This perennial herb or small shrub is famous for its rapid plant movement—the compound leaves fold inward and droop when touched, disturbed, or exposed to heat, recovering within minutes. Native to the Americas but now pantropical, it has bipinnate leaves and small pink or purple flowers in globular heads. The fruits are clustered pods with bristly margins. The plant's remarkable nyctinastic movement is achieved through changes in turgor pressure in specialized cells at the base of the leaflets and leaf stalks.

Phylogeny and Classification

Fabaceae is a member of the order Fabales within the rosid clade of eudicots. The family is monophyletic, meaning all members descend from a common ancestor. Molecular evidence suggests that the legumes diverged from other rosid lineages approximately 60 million years ago, during the Paleocene epoch, with rapid diversification occurring during the Eocene and Oligocene.

Traditionally, the family was divided into three subfamilies based primarily on flower morphology: Papilionoideae (or Faboideae), Mimosoideae, and Caesalpinioideae. However, molecular phylogenetic studies have revealed that while Papilionoideae is monophyletic, the other two traditional subfamilies are not. This has led to a revised classification system that recognizes six subfamilies: Papilionoideae, Caesalpinioideae (including the former Mimosoideae), Detarioideae, Cercidoideae, Dialioideae, and Duparquetioideae.

Position in Plant Phylogeny

- Kingdom: Plantae

- Clade: Angiosperms (Flowering plants)

- Clade: Eudicots

- Clade: Rosids

- Order: Fabales

- Family: Fabaceae

Evolutionary Significance

The Fabaceae family represents one of the most successful evolutionary radiations among flowering plants. Key evolutionary innovations include:

- Nitrogen fixation: The symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing bacteria has allowed legumes to colonize nitrogen-poor habitats and has contributed significantly to their ecological success.

- Diverse floral morphology: The evolution of specialized flower structures, particularly the papilionoid flower with its mechanism for precise pollen deposition, has facilitated efficient pollination by insects.

- Chemical defenses: The production of diverse secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, non-protein amino acids, and protease inhibitors, has provided protection against herbivores and pathogens.

- Seed dispersal mechanisms: Various modifications of the basic legume fruit have evolved to facilitate different modes of seed dispersal.

- Leaf modifications: Adaptations such as compound leaves, leaflet movements, and modifications for climbing or water conservation have allowed legumes to thrive in diverse environments.